‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together’.

— African Proverb

Recently, I stumbled upon a topic that sparked more than just my curiosity, it lit a fire of reflection. The title? The real challenges of cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork. Sounds fancy, right? However, behind that polished phrase lies a messy, thrilling, sometimes chaotic reality that many of us face but rarely unpack.

Introduction:

Cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork refer to collaborations that span across different departments within a single organization or between multiple organizations, respectively (Huxham & Vangen, 2005). These forms of collaboration are increasingly popular in today’s interconnected work environments, promising broader perspectives, faster problem-solving and more innovative solutions.

In theory, cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork sounds like a dream come true. We bring together diverse talents from different departments or organizations, and boom! Instant innovation, faster problem-solving and broader perspectives.

But in practice? It is often more like assembling a band where the drummer follows jazz, the guitarist loves metal, and the singer only sings karaoke hits.

The potential is there and yes and also the headaches. In this essay, we will explore the major challenges of cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork, supported by research and real-life examples, with a dash of wit to make the reading easier to digest.

1. Misaligned Goals and Priorities

In cross-functional teams, members may come from marketing, finance, engineering and other departments, all with different success metrics. While marketing may aim to boost brand awareness, finance focuses on cost efficiency and engineering just wants to build something that does not explode. The same goes for cross-organizational teams, each organization often has its own objectives, stakeholders and risk appetite (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967).

In my experience, this disconnect showed up when I was working on a project involving multiple stakeholders. Everyone nodded enthusiastically in the meetings. Though when it came time to act, each department retreated to its own comfort zone, prioritizing its own internal deadlines. It was like trying to row a boat with everyone paddling in different directions, lots of splashing with not much progress.

In the middle of the operation, the project stalled. No one seemed willing to take the wheel. The energy died down, emails were answered with vague promises and the updates quietly gathered dust in everyone’s inbox.

Instead of watching it fade away, I decided to take initiative. Drawing on my role and network, I slowly started stitching the pieces together. I followed up personally with each stakeholder, clarified deliverables and even helped reframe certain parts of the procedure to align with different departmental goals. Bit by bit, the tide started to turn.

Slowly, people re-engaged not because they were told to, it is because they saw the momentum building. What was once a tangled web of crossed wires became a coordinated effort. And in the end, the project got delivered not perfect, not easy, but real and complete.

The lesson that I learned is, sometimes the spark does not come from the group. It comes from a person willing to relight the fire and then fanning it just enough for everyone else to feel the warmth.

- Leadership Confusion

Who is actually in charge? Cross-functional and cross-organizational teams often suffer from what I call ‘leadership spaghetti’, a tangled mess of dotted lines, reporting structures and conflicting instructions. According to a study by Ancona and Caldwell (1992), unclear authority is a major barrier in cross-functional teams.

At one point, I noticed something was off in a collaborative assignment between us, the students and a professor. Our professor requested us to submit an Intellectual Property (IP) idea. Somehow, the message got lost in translation. My classmates assumed their earlier assignment submission counted and I had this weird feeling that something was off. That feeling intensified when our professor launched a copyright awareness campaign in May, yet nobody was moving. Turns out, the IP submission was a separate task altogether. Oops.

This is a classic example of how communication, as well as the lack thereof, affects progress in cross-functional teams. Different roles come with different assumptions. Clear information becomes distorted like a broken telephone, especially when everyone is already juggling different expectations. When roles are not clearly defined or when everyone thinks someone else is responsible, things slip. According to Salas et al. (2005), elements such as effective team leadership and mutual performance monitoring are among the five key components of team effectiveness. Without these elements, teams are prone to losing direction and motivation.

The lesson that I learned is, even in academic collaboration where everyone is technically ‘on the same team’ can fall apart without communication. It is not about assigning blame, it is about stepping up when the silence gets too loud. Sometimes, the most important leadership move is not a grand gesture. It is simply asking the right question at the right time.

- Communication Breakdowns

Different professions and organizations often speak different ‘languages’. What a developer calls a sprint, a marketer may interpret as a campaign, and the legal team might hear it as a red flag. Miscommunication is not just likely, it is guaranteed.

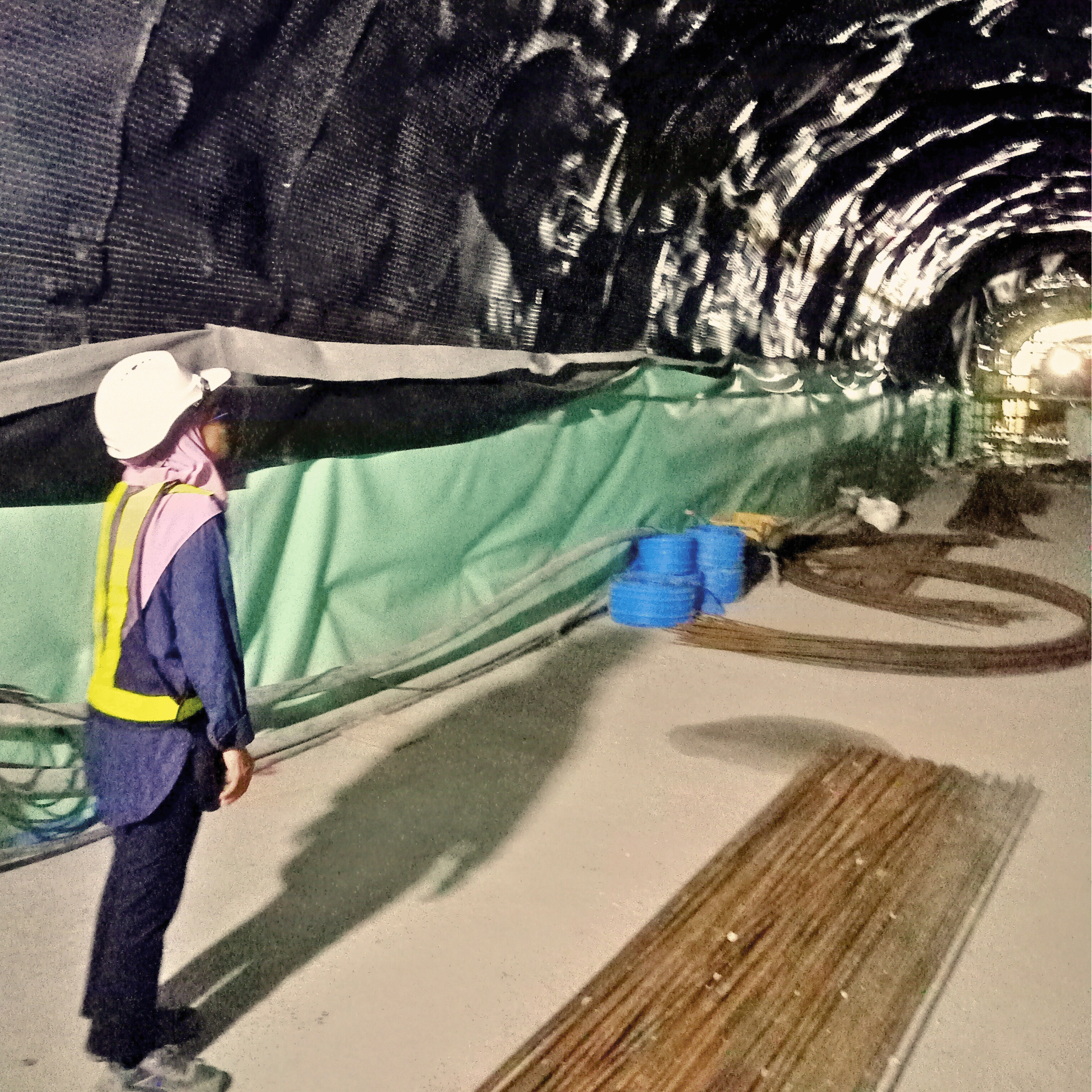

Another classic example from my own experience came during a project involving the design of a raw water pipeline which required inter-state transfer. One of our designers proposed a 3 meter diameter pipeline. Yes, three meters. At the time, this size had not been constructed anywhere in the region. In fact, I was told it would have been the first of its kind in Asia.

The technical team blinked. Silence fell. A few engineers leaned in for a closer look at the drawing, others double-checked the figures and more than one person quietly wondered if it was simply a typo. Surely, no one meant three meters? But no, the proposal was bold, intentional and technically sound.

However, the real challenge was not the mathematics nor the structural calculations or hydraulics. It was getting everyone on the same page in aligning different understandings, balancing how each team viewed the risks, and managing expectations. Every team had its own way of seeing the project, shaped by their background and comfort level.

Convincing people took time. We had to break down the technical concepts into something relatable, present international benchmarks, run simulations and build a proof of concept to ease fears. And while we spent time refining the design, we also spent much time engaging in what I can describe as ‘engineering diplomacy’ which is balancing technical ambition with stakeholder comfort zones. In the end, the pipeline was built and it worked.

The biggest lesson that I learned was about people. The hardest part was building trust. Trust that innovation can be safe. Trust that risk can be managed. Trust that someone else’s wild idea might just work.

That moment reminded me that in cross-functional and cross-organizational teams, progress often depends less on technical capability and more on our ability to connect, communicate and champion a shared vision. Even when that vision seems unbelievable at first glance.

- Cultural Differences and Organizational Silos

But even with a clear leader in place, not all problems vanish. Sometimes, the real challenge is not ‘who leads’. It is how everyone thinks, decides and communicates.

Which brings us to the final challenge, navigating cultural differences and organizational silos something I experienced firsthand during one of the boldest projects I have ever been involved in. We were trying to introduce a 3 meter diameter pipeline something that, at the time, had never been attempted in Asia. The technical challenge was one thing but getting everyone on the same page? That was the real engineering feat.

Different departments held onto their familiar ways of working. Some guarded information like treasure, others were reluctant to adopt new tools or change processes. Each organization or department acted like an island. This silo mentality led to delays, duplicated effort and frequent misunderstandings. It took deliberate effort, regular check-ins, team-building sessions and leadership intervention to shift the culture from isolation to collaboration.

Conclusion: The Art (and Chaos) of Teaming Across Borders

At first glance, cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork promises synergy, speed, and spectacular results. The concept feels like a corporate utopia until you are the one stuck in the middle trying to get marketing, finance and engineering to agree on the size of a pipeline or the deadline of a project.

As we have explored, these collaborations come with their own unique set of challenges. The challenge comes from clashing goals and unclear leadership to confusing communication channels and deep-rooted cultural silos. They don’t just test our skills as a professional. They test our patience, our adaptability and even our sense of humor.

However, here is the beauty of collaboration. When it does work, it works brilliantly. When teams manage to overcome the chaos, align their objectives and genuinely listen to one another, the results can be groundbreaking. Just like the first 3 meter pipe we built against all odds. The lessons from that project were not just about engineering. They were about translating innovation across disciplines, building trust among doubters and leading when no one is quite sure where the map is.

At the end of the day, cross-boundary teamwork is less about perfect harmony and more about learning to jam with different instruments. It’s messy, noisy, sometimes off-key but if we keep at it, we just might make music no one has ever heard before.

Final Reflection

Reflecting on these experiences, I realize that success in cross-functional and cross-organizational teamwork does not depend on eliminating conflict. It is rather about learning how to navigate through it. How to build bridges not walls between departments, between organizations and most importantly, between people who think differently.

Sometimes, we will be the engineer trying to explain a pipe that no one believes exists. Other times, we will be the only one in the room who realizes the assignment has not been submitted. Either way, we learn to ask questions, to clarify assumptions and to keep the team moving forward even when everyone else seems stuck.

For me, these lessons are not just theoretical. They have shaped how I lead, how I communicate and how I collaborate across boundaries. And as I step into roles that may involve entrepreneurship, coaching, administration and research, I carry this mindset with me.

At the end of the day, teamwork across departments or organizations is a bit like a group trip. We need a clear plan, someone to hold the map and most importantly, the willingness to enjoy the ride, even when someone forgot to bring snacks.

Because in the end, the most valuable team players are not those who have all the answers, but those who bring people together to find the answer. Even if that means being the one who brings the snacks on the road trip no one mapped properly.